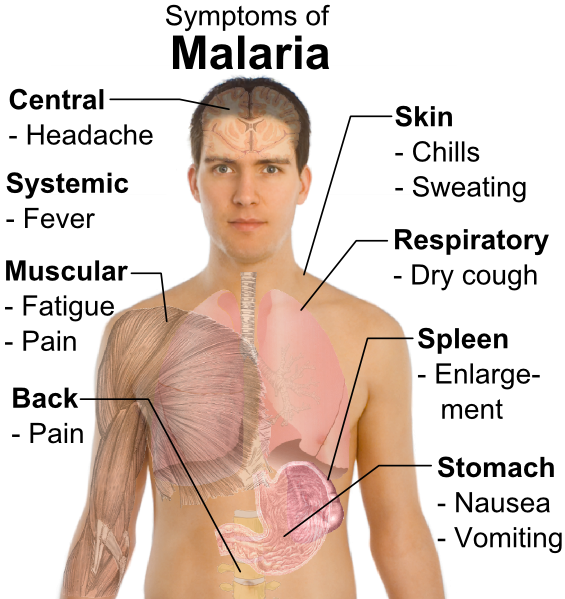

In the onset of Lassa fever, the symptoms easily could be mistaken for malaria.

In the onset of Lassa fever, the symptoms easily could be mistaken for malaria.

Anti-malarial drugs are prescribed, but the patient doesn`t seem to show improvement. the health, instead, is deteriorating.

Further actions are made to combat symptoms that mimic those of other diseases, such as yellow fever and dengue fever. but nothing seems to take as the patient quickly approaches death.

As soon as five to seven days after infection — when the telltale signs of Lassa, a viral hemorrhagic fever, present themselves — it`s often too late.

Endemic to portions of West Africa, Lassa fever is estimated to infect anywhere from 100,000 to 500,000 people on an annual basis and official projections place the mortality rate in the 2 percent to 5 percent range. However, some in the medical field say those estimates are crude and that the cases, and especially the mortality rates, are much greater with 10 times the number of fatalities.

“I think what we believe is that (Lassa fever) is severely under-tested and severely undiagnosed,” said Douglass Simpson, president and chief executive officer of Broomfield-based Corgenix Medical Corp.

Corgenix, the locally based maker of diagnostic tests, is one member of a multidisciplinary team that has spent the past six years addressing that concern.

As a result of federal funding, a team of businesses and academics have worked in Sierra Leone, Africa, and surrounding areas to develop an array of diagnostic tests for deadly Lassa fever. the program`s efforts also could result in potential therapeutics and vaccines and could play a role in the U.S. government`s biodefense efforts as well, Simpson said.

Seeing there were really no means of immediately diagnosing Lassa — let alone a dedicated treatment for the disease — the National Institutes of Health awarded a grant to Tulane University, Corgenix and others to develop new recombinant proteins and viral detection products that were deployed in Africa for clinical testing.

About $25.8 million in grants have been awarded through National Institutes of Health agencies for the three Lassa projects that started in 2005 and carry through 2015, Simpson said. of those funds, about $3 million went directly to Corgenix, he said.

The team — which also includes Autoimmune Technologies LLC, Vybion Inc. and University of California-San Diego researchers, among others — is in the middle of a five-year grant to further develop the test kits, finalize the clinical studies and move the products into commercialization.

A third arm of the program involves research dedicated to creating therapeutics and possibly a vaccine for the disease that is treated now intravenously with ribavirin — an antiviral taken orally to treat hepatitis C, Simpson said.

While the results from the program should benefit Corgenix`s earnings and could help the United States diagnose a Class a biological agent in a matter of minutes, the greater cause of saving lives and advancing the on-site technologies sit at the heart for Matt Boisen, Corgenix`s research and development manager and a lead scientist in the Sierra Leone program.

“We`re really hoping that we can find an avenue to get these diagnostics distributed throughout West Africa,” he said.

Boisen earlier this month was at his Broomfield lab preparing prototypes for Tulane University professor Robert Garry, who will travel to Sierra Leone in a couple of weeks. the stateside work of Boisen and others does not involve any live samples of the virus, but rather irradiated samples or recombinant agents, Corgenix officials said.

In the coming months, Boisen expects to return to the West African country to further pre-clinical testing. the work he`s been involved with already has left a lasting impression.

“There`s a really huge public health awareness push, especially with the health-care workers and midwives, because it could be very fatal in pregnant women,” Boisen said, noting a 90 percent mortality rate for women in their third trimester.

Boisen relayed one account of a woman in her third trimester of pregnancy who arrived very ill at the Lassa ward in the city of Kenema. She was diagnosed and treated.

But then there are the other cases — those that all too often include young children — where the sample is taken, the test is run, but the patient dies before treatment is administered.

“There`s big highs and there`s big lows,” Boisen said.

As a means of shifting that balance toward more positive results, a number of the program`s research efforts are expected to be published soon in medical journals, said Luis Branco, a scientist at New Orleans-based Autoimmune Technologies.

“There`s been really tremendous progress. I think we`ve really changed the way that Lassa virus is diagnosed and therefore treated,” he said. “… I think that we have really gleaned new insights into the virus itself and how it operates at a molecular level and, at the same time, how to use that information.”

On a local level, Branco feels the program has helped to improve infrastructure in a country still recovering from the ravages of an 11-year-old civil war. the team invested in the diagnostics, lab equipment, power supplies and also has employed locals to assist in the efforts, he said.

“We try to develop the infrastructure in the country, such that we can provide some sort of self-sufficiency,” he said.

The work for Corgenix and crew is far from over, although officials hope to have a slate of blood diagnostics — including a rapid, 10-minute test and more comprehensive, two- to three-hour tests — ready for commercialization later this year, Simpson said.

“Ultimately, where Corgenix would like to go would be to have a battery of products, perhaps even configured on the same little cassette where we could detect three or four different viruses,” he said.

Corgenix also expects to further diagnostic testing for other deadly viruses, he said.

Corgenix received the entirety of a $590,000 grant for a similarly focused Ebola virus and Marburg virus program that runs from 2010 to 2012, Simpson said.

“You`re never going to eradicate the virus,” he said. “What we want to do for the next 10 years is just get into a system where we can diagnose them quickly, treat them quickly and reduce the mortality rate.”