LOUISVILLE - Sarah Vanegas wanted quick relief for her 17-year-old daughter’s sore throat and congestion, so instead of trying to schedule a visit with her doctor, she went to a Take Care Clinic inside a nearby Walgreens where her daughter could be seen quickly.

“Sometimes with the pediatrician, you’re waiting 40 minutes. here, we were in and out in 20 minutes,” said Vanegas, of Louisville, whose daughter, Lindsay, was prescribed an antihistamine and nasal spray for allergies. “For the symptoms she had, I felt very comfortable with this.”

Families seeking faster care close to home have helped push up the number of retail clinics dramatically across the nation – from about 200 in October 2006 to more than 1,200 at the end of 2010.

That’s according to the research and consulting firm Merchant Medicine, which lists 40 retail clinics in Kentucky and anticipates more clinics across the nation this year.

The clinics are usually staffed by nurse practitioners and located in grocery, drug and department stores, often close to where medications are sold.

Visits are comparatively cheap; a 2009 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine put the cost a typical visit – including evaluation, medications, labs, tests and other services – at $110 in the average retail clinic, $166 in a doctor’s office, $156 in an urgent care center and $570 in an emergency room.

“The biggest thing these clinics fulfill is a convenient place to go for a minor illness,” said Tom Charland, Merchant Medicine’s chief executive officer. “And people truly are saving money.”

But some doctors contend the clinics cause more problems than they solve.

Critics say they interrupt relationships between patients and doctors and create potential for conflicts of interest between stores and clinics. They say doctors who know their patients offer better care, less chance of costly follow-up visits and a greater likelihood of finding potentially serious medical problems.

“There might be something that presents as a minor complaint but is in fact the tip of the iceberg,” said Dr. Gordon R. Tobin, president of the Kentucky Medical Association. “Physicians have the gold standard in education and training.”

Kentucky adopted a regulation in August saying retail clinics must restrict services to a list of minor illnesses, screenings and preventive care such as flu shots, and they can’t provide ongoing treatment for chronic illness.

That state also required retail clinics to tell patients that they don’t have to buy medications from the host store.

Meanwhile, clinics are prompting some doctors to change their methods to meet the needs of patient seeking greater convenience.

Glen Stream, president-elect of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said more doctors are providing services such as after-hours and weekend care and same-day appointments.

“If the doctor’s office is only open 9 to 5, and kids are in school and parents are at work, that’s not meeting the need,” Stream said.

Studies find quality

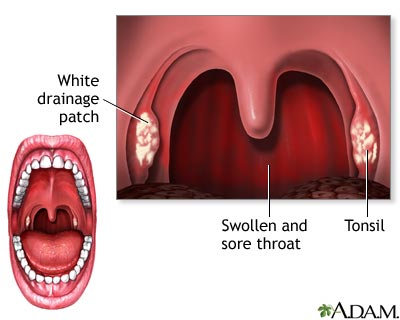

Charland said five illnesses make up the majority of retail clinics’ workload: strep throat; pink eye; and infections of the ear, sinus and female bladder. Studies show clinics generally provide quality care for such conditions.

A report last year by the Rand Corp., a non-profit policy and research organization, examined several studies and said initial evidence suggests quality at retail clinics “is comparable to that provided in other health care settings.”

One study looked at three conditions – ear infections, sore throat and urinary tract infections – and found that “quality scores” were similar at retail clinics, physician offices and urgent care centers – although retail clinic patients were less likely to undergo urine tests for infection.

The report also cited three studies examining rates of repeat visits and follow-up care, possible indicators that care during the first visit was incomplete. two studies found similar rates at retail clinics and other settings, and the third found a 2 percent higher rate for retail clinics.

Charlotte Beason, executive director of the Kentucky Board of Nursing, said she knows of no disciplinary actions connected with nurse practitioners at retail clinics, who are required in Kentucky to have written agreements with doctors, who aren’t required to be on site.

Nurse Jill Johnson, market manager for clinic operations at Take Care Health Systems, said nurses know what they can handle and what they can’t – and they call 911 if someone comes in with a serious symptom such as chest pain.

Recently, retailers such as Walmart have begun partnering with hospital systems to run their clinics. Typically, most retail clinics – are subsidiaries of their host stores.

“We believe our customers are happy to be helped by local organizations they already know and trust to provide health care,” said Bruce Shepard, director of health care innovations for Walmart, which has partnered with Baptist Hospital East and others. “We know that the clinics mean a great deal to our customers from a convenience standpoint.”

Economics vs. care

Charland said doctors’ objections to retail clinics come down to one thing: “Economic consequences.”

But doctors say it’s not that simple.

Dr. Emily Johnson, a Louisville pediatrician, acknowledged that competition is one issue, saying, “From a business standpoint, I really would prefer they didn’t exist.”

But she said quality is a larger issue.

She said children’s medical care can suffer when nurses aren’t aware of patient information such as whether immunizations are up-to-date. And she said many nurses at retail clinics have no specific training in children’s care, while “pediatricians have three years or more of pediatric training.”

She said many families that bring children to the clinics wind up coming to her afterward – driving up their costs. She estimated that in the past six months, she’s spoken with about 35 families whose children have been seen in retail clinics, and “at least 25 of them were in the office to follow-up or because they wanted our second opinion.”

She recalled one teen seen twice over six months at a retail clinic, diagnosed with bronchitis both times, and given antibiotics and steroids. The steroids helped, she said, but the antibiotics didn’t. When she saw him, she looked at his records from previous years and realized asthma was the cause of his symptoms, not infection. “I put him on a daily controller medication as well as a rescue inhaler and his symptoms resolved within a few days,” she said.

Doctors also said potential problems such as medication allergies may go undetected at retail clinics.

“People want convenience,” Tobin said. “But there is a price.”

Doctors also said retail clinic nurses may over-prescribe antibiotics, which can lead to the growth of drug-resistant superbugs such as MRSA.

But a 2009 study found no evidence of this, saying 25 percent of patients with sore throats received antibiotics at retail clinics, compared with 29 percent at doctor’s offices.

Tobin said the KMA supports the state’s efforts to restrict the scope of care for retail clinics, especially as more clinics nationally explore handling routine, ongoing care associated with chronic conditions such as diabetes.

Stream, of the national physician group, agreed that doctors are best at handling the complexities of chronic illness.

“This often gets seen as a turf battle. But most family doctors are busier than they can be,” he said. “It’s not just like they’re worried about someone taking their business. … It really is a genuine concern about what’s good for the patient.”