images/stories/2011/03March/030411bettyjones2.jpg

South Boston resident Betty Jones has always maintained a positive outlook on life, and she has always been proactive when it comes to living a healthy lifestyle.

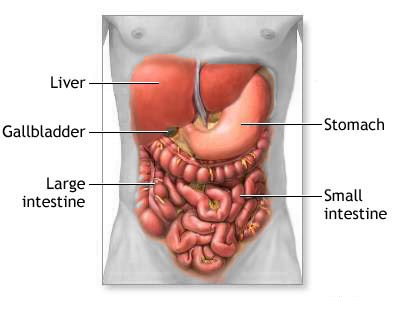

That positive outlook was put to the test several years ago when Jones was diagnosed with Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH), a genetic disorder and leading cause of iron overload disease, but she has persevered and now wants to communicate the lessons she’s learned in fighting the disorder to others.HH is not rare, with more than 1 million people in the United States suffering from the disorder, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.But, public awareness in regards to its symptoms, diagnosis and treatment lags behind that of other diseases and disorders, according to Jones.“The gene was discovered in 1996, and prior to that, it was considered a rare, fatal disorder of mostly older men,” said Jones, who was first diagnosed with the disorder in 1999.further research has since revealed it to be the most common genetic disorder among Caucasians in the United States, she added.“In a normal person, the body sloughs off excess iron, more than your body needs, but with this disorder, the iron doesn’t go, and it’s stored somewhere in the body,” said Jones in describing the effects of HH.Excess iron can be stored in vital organs such as the pancreas, and the effects are much the same as a car rusting, according to Jones.“Much like a car that begins to rust, that organ begins to rust, and of course it causes damage, and ultimately it could be fatal,” said Jones.“The disorder itself is not fatal, but the problems it causes can be fatal if left untreated.”Jones recalled her symptoms as similar to others with the same disorder.“My symptoms were like most people have, a chronic fatigue, and it can magnify itself through heart problems and diabetes in particular as well as arthritis, and it can cause arrhythmia which (in turn) can cause heart attacks.”Other signs may include abdominal pain, elevated liver enzymes, cirrhosis, emotional changes, depression and hair loss.Disheartening diagnosisJones said she was initially misdiagnosed, something that has happened frequently with HH patients.“I know someone who had gone to 12 different doctors before it was diagnosed,” she pointed out.“When I was first diagnosed I was going to a doctor in Roanoke who was doing these kinds of tests automatically, and when she did it, and results came back, she said it could be colon cancer.”That’s when family history and personal research kicked in, and Jones got a handle on how to live with the disorder.“From the time the doctor told me I could have colon cancer until the gastrointerologist reported I was cancer free was only four months,” recalled Jones.“But, it seemed like an eternity, and reading on a medical website that HH was a rare and often fatal disease made it even worse.“Since that time, with the advances in research and testing, I have learned that diagnosed in time, this disorder is not fatal. in fact, in some cases the damage can be reversed if found in time.”At present, the only treatment for the disorder is phlebotomy, according to Jones.“There’s no pill, nothing like that,” she noted, recalling a normal woman’s iron level as being between 75-200 (ng/ml).“When mine was discovered it was 600, which is three times greater than normal.“Once I was diagnosed, I had to give a pint of blood a week for four months.“A normal person can’t give blood but once every other month, but instead of making me feel tired, it made me feel better every time I did it.“I had aching joints, but fortunately it didn’t damage any of my organs, so I’m lucky.”“Some people have so much iron built up in their bodies that they set off metal detectors in airports and have to carry a letter from doctors explaining why.“Mine never got that bad, and I feel very, very fortunate.”Jones counts herself among the lucky ones who had their disorder diagnosed in time.“Once they got my iron level down to a normal level, I go periodically to get my blood work done,” she said.Learning about Hereditary HemochromatosisJones has attended two international patient conferences focusing on HH at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md.“During the conferences I’ve attended, patients have told horror stories about being misdiagnosed and the number of doctors they have visited (as many as 15) before receiving help,” she said.“I consider myself blessed because every medical professional that I have seen locally has been great. they have listened to me, referred me when necessary, read the information I have given them, treated me and monitored my progress.“And, when I say medical professionals, this includes the nurses, lab personnel, X-ray technicians and office staff.”Knowledge is keyJones said she has had everything from a brain MRI, organ scans, X-rays and numerous blood tests, and except for some arthritis, all indicate she is in good health, as long as she monitors her iron level.she emphasized there are specific tests available to diagnose Hemochromatosis, and patients need to ask for them specifically.“I want to get the word out, there are people with similar symptoms who may not have this, but why not get it checked out,” she urged.“I believe it’s better to be tested and find out you don’t have a problem than to assume you don’t have it and end up with life threatening medical issues.”Jones asks that anyone with comments or questions call her at 434-222-7227.

< Prev next >