By By DAVID PEPIN Mike and Pam Noble.

By By DAVID PEPIN Mike and Pam Noble.

Over the past few years, the media has been full of stories of breast cancer and prostate cancer patients who have beaten their diseases and gone on to continue living healthy and productive lives.Michael Noble is hoping to see a series of similar stories about people who have beaten pancreatic cancer.He’s hoping to be one, too.

Unlike breast and prostate cancer patients, however, the numbers are not in his favor.These days, the 58-year-old management consultant is driven by the number 5: the percentage of pancreatic cancer patients who live five years after their original diagnosis, considered a long-term survival benchmark by medical professionals.“I firmly believe I’ll make it to long-term status. until somebody tells me otherwise, that’s how I’m proceeding,” he says, relaxing Monday evening in his living room at 35 Signal Ridge Way after arriving home from the Boston office of Career Management and Executive Development, a firm in which he is a partner.

The battle for awarenessWhile fighting his cancer with drugs and chemotherapy treatment, Noble is also focusing on increasing people’s awareness of the disease, the fourth-leading cause of cancer death in the United States, according to the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN), on the Web at pancan.org.he was among 100 patients and family members of those touched by the disease who gathered at the Statehouse Nov. 13 to participate in PurpleLight, a vigil sponsored by the Providence affiliate of PanCAN to advocate for more funding to research and find a cure as part of November’s Pancreatic Cancer Awareness Month campaign. the event included the lighting of the Statehouse dome in purple.“There have been tremendous advances made in the treatment of breast cancer over the past 30 years, and there are nearly three million breast cancer survivors. Unfortunately, not many survive pancreatic cancer,” he says,Noble is one of an estimated 43,140 new cases of pancreatic cancer diagnosed this year, according to the American Cancer Society, which estimates 209,060 new cases of breast cancer this year.the society estimates 36,800 people will die of pancreatic cancer this year, slightly less than the 40,230 estimated breast cancer deaths for the year..

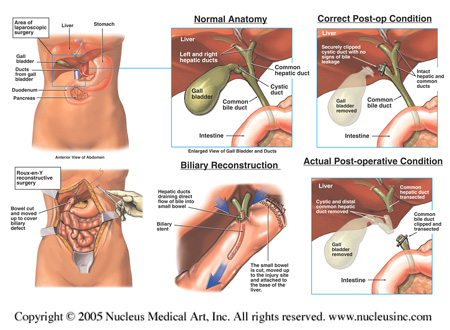

The late-night warningNoble first sensed something wrong on the night of Aug. 16, just two days after the wedding of his oldest son, Matthew.“In the middle of the night, I was awakened with what I though was acid reflux,” says Noble, adding he had been in excellent health and had never experienced those symptoms.Fearing the pain in his sternum could be a heart attack, his wife, Pam, called an ambulance, and he was taken to Miriam Hospital in Providence. he was held for two days of tests, which found no cardiac abnormalities.“I had six more attacks over the next two weeks, always painful and always late at night,” he says.Those incidents prompted a visit to a gastroenterologist for endoscopy, ultrasound and a CAT scan. he received his test results and diagnosis on Sept. 9.“I could see lesions on my pancreas. they weren’t biopsied, but I was told there was a 98 percent chance they were malignant,” he remembers.Noble moved quickly to have further evaluation done at Rhode Island Hospital, where he discovered he was a candidate for the Whipple procedure, the most effective form of pancreatic cancer surgery yet developed.“In only about 15 percent of cases can they do it, if it hasn’t metastasized,” he says.On Sept. 30, Noble underwent the Whipple at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Dr. Carlos Fernando Del Castillo removed one third each of his pancreas, upper intestine and stomach, and his entire gall bladder in a six-hour procedure.“When you have to have complex surgery, you want to go somewhere where they do a lot of it,” says Noble, adding that Del Castillo performs the surgery about 150 times a year.“He’s a compassionate, empathetic surgeon who really took us under his wing.”While most Whipple patients require 14 to 20 days of hospital recovery, Noble was able to go home in five.“I had no other health issues, and I was relatively young to have pancreatic cancer,” he says.Alas, Noble’s bill of health was not quite clean.“Because it had spread into my lymph nodes, I had 23 removed, and I had cancer in nine of them. I was hoping pathology would find the tumors had closed margins that were well contained, but some were open on the ends,” he says.“When that happens, you have to go into chemo.”

The treatmentNoble is currently visiting Mass General once a week for an infusion of gemcitibine, a cancer-fighting drug. he has just begun the second of three weeks on, one week off cycles.“If everything works well, I go into intensive radiation and chemotherapy,” he says without a hint of irony.Noble has already had a port implanted in his chest in preparation for the five-day-a-week radiation treatments and the chemotherapy drugs, to be injected into his veins via the port, he will have to carry in a fanny pack at all times. this ritual is scheduled to continue for six weeks.“Assuming all that works right, I’ll have another staging, or exam,” he says.If he tests negative for cancer, he will undergo a staging every three months for the rest of his life.“That’s what you’re hoping for,” he says.Living under a death sentence Noble is under no illusion that he will be the cancer-free miracle of his time. While he is familiar with stories of pancreatic cancer patients who have beaten the odds and survived five years (and one who has lived 11 years and counting), he has also seen a friend die just six months after being diagnosed.“It was like hearing a death sentence. I knew vaguely that the survival rate wasn’t high,” he says of his thoughts after receiving his diagnosis.“It’s upsetting, but there’s a chance.”The father of Matthew, 30; Kyle, 27, and Hillary, 21, Noble continues to work at his business, some days at home, some days in Boston, where he now drives instead of taking a train as a concession to his compromised immune system.“I don’t want to sit on a train and take a chance of catching something from somebody,” he says.A valuable resource, he says, is “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer,” by oncologist Siddartha Mukherjee, who was interviewed on a National Public Radio (npr.org) podcast Nov. 17.Another comfort to him is the timing of his current treatment, whose next week off will include Christmas.“I have a general lethargy,” says Noble, who can work for two to three hours after a treatment before nausea forces him to rest. “But when you have a week off, it’s great.”

View more articles in: