Posted on: Friday, 24 December 2010, 07:56 CST

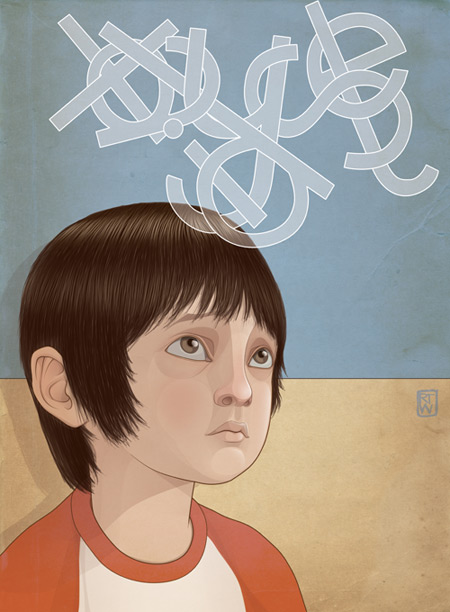

(Ivanhoe Newswire) – by using sophisticated brain imaging, Stanford University School of Medicine researchers are able to predict with 90 percent accuracy which teenagers with dyslexia could improve their reading skills over time.

This is the first study to identify specific brain mechanisms involved in a person’s ability to overcome reading difficulties. It has potential to lead to new interventions to help dyslexics better learn to read."This gives us hope that we can identify which children might get better over time," Fumiko Hoeft, MD, PhD, an imaging expert and instructor at Stanford’s Center for Interdisciplinary Brain Sciences Research, was quoted as saying. "More study is needed before the technique is clinically useful, but this is a huge step forward."

Dyslexia affects 5-17 percent of U.S. children, and is a brain-based learning disability that impairs a person’s ability to read. Affected children’s ability to improve their reading skills varies immensely, with about one-fifth able to benefit from treatment and develop adequate reading skills by adulthood. Up to this point, what happens in the brain that allows for improvement is unknown.

Previous imaging studies have shown greater activation of the inferior frontal gyrus (part of frontal lobe) in children and adults. Experts hypothesize that greater involvement of this part of the brain during reading is related to long-term gains in reading for dyslexic children.For this study, Dr. Hoeft and colleagues aimed to determine whether neuroimaging could predict reading improvement and how brain-based measures compared with conventional educational measures.

The researchers gathered 25 children with dyslexia and 20 children with typical reading skills — all around age 14 — and assessed their reading with standardized tests. they then used two types of imaging, functional magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging (a specialized form of MRI), as the children performed reading tasks. Two-and-a-half years later, they reassessed reading performance and asked which brain image or standardized reading measures taken at baseline predicted how much the child’s reading skills would improve over time.

What the researchers found was that no behavioral measure, including widely used standardized reading and language tests, reliably predicted reading gains. but children with dyslexia who at baseline showed greater activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus during a specific task and whose white matter connected to this right frontal region was better organized showed greater reading improvement over the next two-and-a-half years. the researchers also found that looking at patterns of activation across the whole brain allowed them to very accurately predict future reading gains in the children with dyslexia. "the reason this is exciting is that until now, there have been no known measures that predicted who will learn to compensate," said Dr. Hoeft.

The other exciting implication, Hoeft said, involves therapy. the research shows that gains in reading for dyslexic children involve different neural mechanisms and pathways than those for typically developing children. by understanding this, researchers could develop interventions that focus on the appropriate regions of the brain and that are, in turn, more effective at improving a child’s reading skills.

Hoeft said this work might also encourage the use of imaging to enhance the understanding (and potentially the treatment) of other disorders. "in general terms, these findings suggest that brain imaging may play a valuable role in neuroprognosis, the use of brain measures to predict future reductions or exacerbations of symptoms in clinical disorders," Dr. Hoeft explained.

SOURCE: the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online December 23, 2010

Source: Ivanhoe Newswire

More News in this Category