Study Shows Denufosol Delays changes in Lungs that Lead to Airflow Obstruction

By Kathleen DohenyWebMD Health News

Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD

Latest Lungs News

Dec. 21, 2010 — an experimental cystic fibrosis drug appears to delay the progression of the chronic disease in children who have normal to mildly impaired lung function, according to a new study.

”These findings are encouraging,” researcher Frank Accurso, MD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, tells WebMD.

The drug is called denufosol.

”The patients who received the drug improved lung function compared to placebo,” he says. when he compared lung function before and after denufosol, “the improvement was 2%.”

‘It’s important because although the improvement was modest, the longer-term effect of the drug could be substantial,” he says.

Doctors believe the lungs of children with cystic fibrosis (CF) are normal at birth and that lung damage occurs early in life. The hope is that denufosol will delay or prevent the progressive changes that lead to irreversible airflow obstruction, Accurso says.

The findings were published online in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Other cystic fibrosis experts say the results look promising for those patients with milder symptoms.

About 30,000 children and adults in the U.S. have cystic fibrosis, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

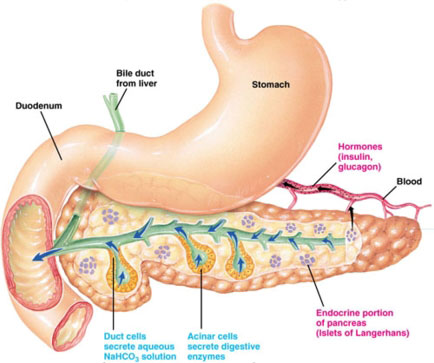

The inherited and chronic disease affects the lungs and digestive system. a defective gene causes the body to make sticky, thick mucus that clogs the lungs and leads to lung infections, and also obstructs the pancreas, leading to digestive problems.

How Denufosol Works

Denufosol works differently than other cystic fibrosis drugs, Accurso tells WebMD. “Most of the other drugs treat the secondary manifestations of CF, such as airway infection and inflammation.”

Denufosol belongs to a class of drugs known as ion channel regulators. In cystic fibrosis, the chloride ion does not flow normally through cell membranes and there is increased sodium absorption, leading to the thick, sticky mucus that in turn increases infection risk.

Denufosol increases chloride secretion, inhibits sodium absorption, and in the process helps clear mucus.

In his study, Accurso assigned 352 cystic fibrosis patients, all age 5 or older, either to get inhaled denufosol or placebo three times a day for 24 weeks. All had early-stage disease, with no or minimal lung function impairment.

For the next 24 weeks, all participants got denufosol.

The researchers measured exhalation rates and lung volume to assess functioning. they monitored the participants for adverse events such as cough, fever, or sinusitis.

After treatment, the denufosol group had an improvement of 2% in their FEV1 — forced expiratory volume, a lung function test — compared to the start of the study. The differences in function between the drug and placebo groups indicated a mild improvement.

The drug did not lead to improvements in other lung function measures or in the rate of infections, a recurring problem for cystic fibrosis patients.

The study, known as TIGER-1, is a phase III trial. Inspire Pharmaceuticals, which markets denufosol, expects to have results from a second phase III trial by early 2011, according to a statement issued by the company.

Accurso was previously a paid consultant for Inspire but currently is not.

Second Opinion

The study findings are cause for optimism, according to Bruce Marshall, MD, vice president of clinical affairs for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

He reviewed the study findings for WebMD but was not involved in the study.

“Denufosol is one of the therapies aimed at the root cause in CF,” he says via email. “We are optimistic it can keep patients with milder symptoms healthier over the long term.”

Another cystic fibrosis expert also finds the results encouraging. “I think the results look promising,” Danieli Salinas, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, who also reviewed the study results.

“The caveat to that is, the results weren’t miraculous,” she says.

While the 2% is not a large improvement, Salinas puts it in perspective. “In terms of CF, anything we can do to preserve lung function over time, we are taking it.”

SOURCES: Frank Accurso, MD, professor of pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver.Bruce Marshall, MD, vice president of clinical affairs, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.Danieli Salinas, MD, pediatric pulmonologist, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; assistant professor of pediatrics, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.Accurso, F. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, online Dec. 17, 2010.©2010 WebMD, LLC. All Rights Reserved.